The two thousand women who volunteered as nurses during the American Civil War came from all walks of life to play a vital role in the war effort. When war broke out, the country’s male-dominated nursing profession was in its infancy and still relatively primitive. The huge escalation in the need for medical personnel during the conflict broke down the barriers preventing women from entering nursing.

Those who wanted to play their part were spurred into action, and these remarkable women made an invaluable contribution. Even so, their hard work and dedication was, largely, historically anonymous. And yet a few individuals contributed so significantly that their experiences have been recognized by history. Read on to learn more about 10 of the greatest nurses of the American Civil War.

10. Annie Etheridge (1839–1913)

Annie Etheridge was inspired to take up nursing by looking after her father on his deathbed, and when civil war broke out, she joined the 2nd Michigan Volunteer Infantry. Nicknamed “Gentle Annie,” Etheridge was loved by all and commended for her bravery under fire.

As an expert horsewoman, she would ride onto the battlefield fearlessly with her saddlebags full of lint and bandages to tend to wounded soldiers. Dramatically, her horse was even shot out from under her – twice. Etheridge’s dedication and courage led to her becoming one of only two women awarded the Kearny Cross, and when she died in 1913, she was buried as a veteran.

9. Clara Barton (1821–1912)

An ardent humanitarian, nurse Clara Barton is probably best known for founding the American Red Cross. Working for the US Patent Office, she was the first woman to hold a senior clerkship in the federal government and was paid as much as her male counterparts.

Nevertheless, Barton gave up her position and joined the war effort. And, selflessly, she declined to take a salary for tending to sick and injured soldiers. Previously, it was unprecedented for women to be on the front-line, but Barton eventually became so trusted that she worked exclusively on battlefields for much of her career.

Because of her dedication and hard work, Barton was known as the “Angel of the Battlefield,” and in 1864 she was made Superintendent of Union nurses. During her nursing career, Barton saw the horrors of sixteen different battlefields and was so moved by her experiences that she became instrumental in encouraging the United States to adopt the Red Cross model she had seen at work in Europe. Ultimately, this led to the US signing the Geneva Agreement in 1882.

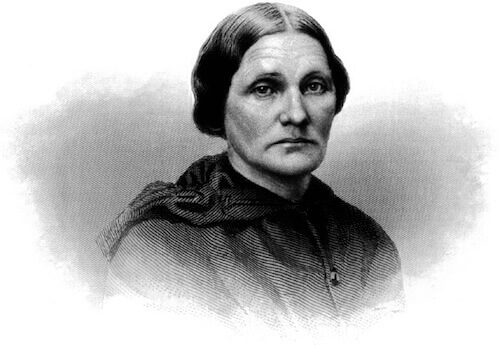

8. Dorothea Dix (1802–1887)

Dorothea Dix became the Union’s Superintendent of Female Nurses in 1861, volunteering her services after the attack on Fort Sumter. Dix took to her rather hazily defined duties and quickly shaped her role, setting a precedent for female nurses for the rest of the Civil War.

Earning the moniker “Dragon Dix,” she managed to convince military officials that women could be competent nurses. She stipulated that only plain-looking women over 30 should be employed in order to avoid some of the stereotypes that prevailed at the time, although these rules were relaxed as the number of nurses recruited entered the thousands.

Dix’s authoritative ways found her clashing with officials and occasionally ignoring administrative details, but nursing care in the army improved significantly under her lead. She was also responsible for bettering working conditions for nurses and hospital conditions for soldiers.

7. Abigail Hopper Gibbons (1801–1893)

When the American Civil War broke out, Abigail Hopper Gibbons anticipated that nurses would be needed, and she joined the fold as a trainee when the United States Sanitary Commission set up a training base at David’s Island Hospital, New York. Gibbons traveled to Washington D.C. to help the wounded and distribute supplies at the Washington Office Hospital. She also helped to set up two field hospitals in Virginia.

When the government took over a hotel and 100 guest cottages to become Hammond General Hospital, Gibbons clashed with Dorothea Dix, then Union Superintendent for Nurses, over the running of the complex and the care of its 1,500 patients. In the end, Gibbons was appointed to the role of head matron. In 1863, the hospital was converted into Point Lookout Confederate Prison, and this was when she left.

6. Mary Ann Bickerdyke (1817–1901)

When she heard about the poor medical care on offer to wounded Union soldiers, Mary Ann Bickerdyke knew that she had to do something.

In her birthplace of Knox County, Ohio, Bickerdyke led a campaign to gather supplies and, leaving her children to be cared for by a friend, delivered these supplies to her nearest Union base in Cairo, Illinois. However, Bickerdyke was so appalled by the squalid conditions she found at the camp that she began tending to the injured, directly violating regulations forbidding her to be there. She led a small team of local lady volunteers, lifted patients’ spirits, and improved cleanliness and recovery rates significantly.

Eventually, Bickerdyke took her work onto the battlefield, where she performed surgeries, moving tirelessly from man to man. When officials objected to her presence, she refused to argue at length, only walking away to continue her work. And she would always return after dark with a lantern and tend to her patients in her DIY hospital.

5. Cornelia Hancock (1839–1926)

Witnessing her brother and other male friends and relatives leave to fight in the American Civil War motivated Cornelia Hancock to get involved as well. When her brother-in-law told her that help was needed near Gettysburg in July 1863, Hancock went, aged just 23, to volunteer. She was turned away by Dorothea Dix, who would only take on older female nurses. However, undeterred, Hancock made her way to the battlefield regardless, and she soon gained praise and admiration for her dedication to caring for the wounded.

Hancock relayed her experiences of the horrors she had seen through detailed letters to her family in which she would describe herself as “dirty as a pig and as well as I have ever been in my life.” Her skills as an organizer and her ability to source supplies made her an invaluable nurse.

Eventually, in 1864, this led her south to Virginia, where there was a large number of war-wounded. Although she drew criticism for living alone with the men in field hospitals, Hancock would always defend her way of life, promising that she would never do anything “rash or romantic.”

4. Phoebe Pember (1823–1913)

Widowed at an early age and unhappy at home, Phoebe Pember accepted an invitation to serve at Richmond’s Chimborazo Hospital in 1862 and joined the war effort. According to reports, Chimborazo was the largest hospital at the time, caring for some 76,000 patients. Pember was in charge of one of the hospital’s five divisions at a time when nursing was still very much a male domain, and she developed “a will of steel under a suave refinement.”

Once, Pember threatened a member of staff caught stealing supplies with a gun, and her gritty commitment gained her respect and acceptance from peers and patients alike. Her memoirs of this time, A Southern Woman’s Story: Life in Confederate Richmond, is still one of the foremost sources for understanding the experiences of upper-class Southern Jewish women before and during the Civil War.

3. Helen Gilson (1836–1868)

Helen Gilson’s involvement with nursing during the Civil War caused her to become a controversial character and a pioneer for the rights of injured black soldiers. When Gilson first heard about the plight of wounded black troops engaged on the front line, she vowed to take action but was counseled against it. Nevertheless, Gilson was undeterred – even though none of her co-workers agreed to help her.

Determined to succeed, Gilson used her feminine wiles to persuade Major General Ambrose Burnside to help her overcome the prejudice of the medical profession. Her hospital for black soldiers was eventually set up, consisting of a square mile of tents. Often she treated the soldiers in temperatures of over 100 degrees.

Aged 29, Gilson wrote about how tired and ill she was becoming. She was suffering from malaria but remained in her post until the fall of Richmond on April 2, 1865.

2. Mary Jewett Telford (1839–1906)

Mary Jewett Telford began teaching at the age of 14 and switched to nursing following the outbreak of the American Civil War. At first, she was not accepted by the US Sanitary Commission because of her age, but like the other nurses on this list, Mary was tenacious. The governor of Michigan, Austin Blair, who was friends with Mary’s father, eventually granted her a special permit that allowed her to get involved.

Telford began working at Hospital No.8 in Nashville and, for eight months, was the only woman in a hospital that cared for six hundred soldiers. One of her roles was to write letters home for soldiers who were unable to write their own, and it is reported that, after the war, many soldiers thanked her for caring for them during their convalescence. Telford left nursing after a year, however, when the job took its toll on her health.

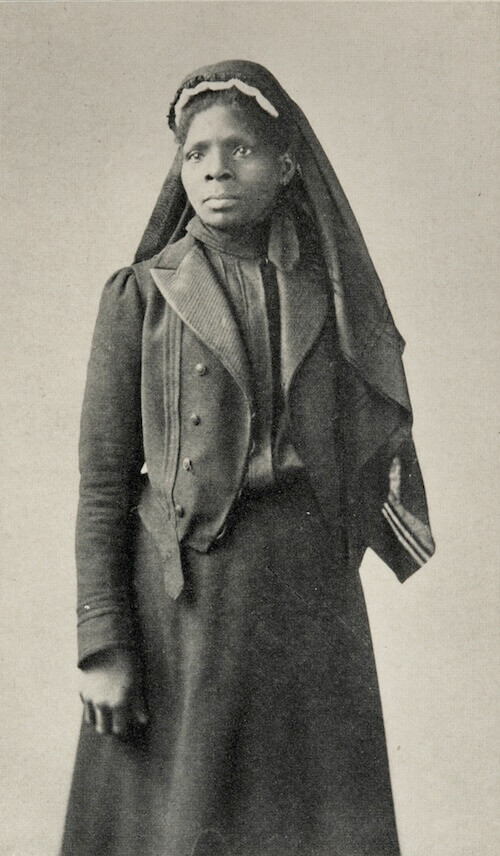

1. Susie King Taylor (1848–1912)

As a freed slave herself, Susie King Taylor became the first black teacher for freed African American students on St. Simon’s Island, Georgia. Before the island was evacuated, Taylor met Edward King, an African American army sergeant, whom she eventually married. Later, she served as a nurse in his (and her brother’s) regiment. On the island, Taylor returned to teaching and taught many of the troops to read and write.

In February 1863, Taylor nursed wounded men returning from a raid up St. Mary’s River. There was a varioloid (a mild form of smallpox) outbreak at the camp and, ignoring the doctor’s orders, Taylor took it upon herself to nurse the men suffering the most. She was also always modest about her endeavors, claiming, “I was always happy to know my efforts were successful in camp, and also felt grateful for the appreciation of my service.”